The United Nations’ flagship Global Resources Outlook report is the portrait of a juggernaut. Due to be published later this month by the UN’s International Resource Panel, it highlights how global consumption of raw materials, having increased four-fold since 1970, is set to rise by a further 60% by 2060.

Already, the technosphere — the totality of human-made products, from airports to Zimmer frames — is heavier than the biosphere. From the 2020s onward, the weight of humanity’s extended body — the concrete shells that keep us sheltered, the metal wings that fly us around — have exceeded that of all life on Earth. Producing this volume of stuff is a major contributor to global heating and ocean acidification, and the rapidly accelerating extinction of plants and animals.

As the UN report spells out, the extractive activities that lie behind the concrete, metal and other materials we use are disrupting the balance of the planet’s ecosystems. The mining industry requires the annexation of large tracts of land for extraction and transportation; its energy consumption has more than tripled since the 1970s.

That upward curve is set to continue. The demand for materials is rising, the quality of ores such as copper is declining, and deeper and more remote mines require extra energy for extraction. More seams will be dug and more mountains moved to bring glittering fortunes to some while many regions, above all in developing countries, become sacrifice zones.

Critical raw materials

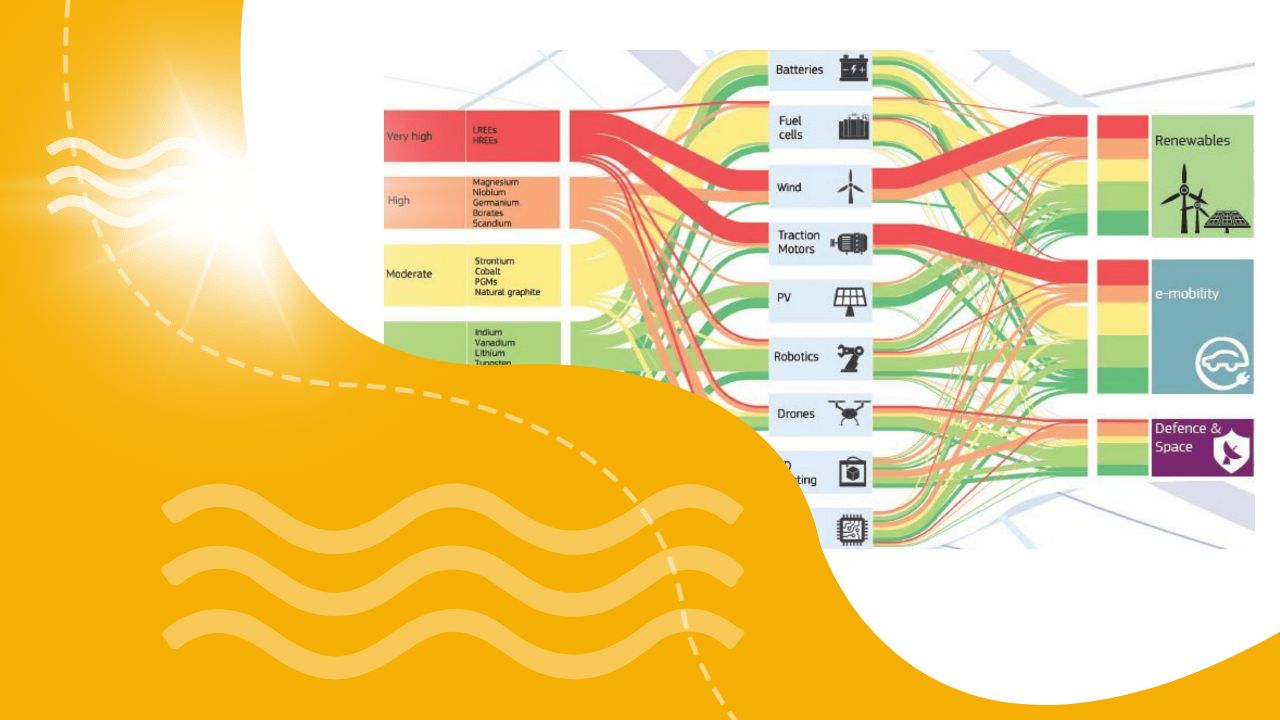

Attention is increasingly focused on a particular class of material. “Critical” and “strategic” raw materials are those that face supply risk either in their scarcity or their geographical concentration, and which the major powers require for their military sectors and for competitive advantage in tech industries. Right now, the race for critical materials is geopolitical: each major power wants to secure supplies in allied countries.

Critical raw materials are indispensable to the green transition too. The EU, for example, deems nickel a strategic material in view of its role in batteries.

A wind turbine can require nine times the mineral inputs of a typical gas-fired power plant, while the average electric vehicle contains between six and ten times those of its conventional counterpart, according to the UN report that is due to be published on February 26.

None of this means that a green economy would use greater quantities of materials than the current fossil fuel-based one. Energy consumption due to mineral demand for energy transition technologies is dwarfed by that which arises from mineral demand for the rest of the economy.

Nonetheless, the mineral demand of the energy transition stokes the mining boom in such sectors as copper and lithium.

Urban mining

Mining must change in order to reduce its environmental impact. On the supply side, recovering minerals from waste goods can be ramped up, for instance by forcing retailers to offer collections of household electronic waste that can be sent for enhanced recycling.

There is scope for urban mining: for example, locating copper from inactive underground power cables or recovering elements from construction waste, sewage, incinerator ash and other garbage zones.

In practice, however, the use of secondary materials relative to newly-extracted ones is declining. The recovery rates of minerals from recycling remain low. Another UN study of 60 metals found the recycling rate for most of them was below one percent.

The current economic system makes extractive mining cheaper and easier than urban mining. Extractive mining involves the purchase of cheap land, often in developing countries.

That land gets dug up, pulverised and processed in a simple flow that is amenable to capital-intensive operations. Urban mining by contrast is often labour-intensive and requires a complex and state-enforced regulation of waste streams.

Urban mining suffers from the refusal of governments to shift taxation from labour to “the use of non-renewable resources”, as Walter Stahel, an originator of the circular economy concept, recommended in 2006. Until robust regulation and taxation is introduced, all forms of circular economy risk unleashing rebound effects.

So, throwing more materials onto the market lowers prices, which tends to expedite economic growth, raise energy consumption, and proliferate environmental harms. In short, there is nothing intrinsically “green” about urban mining or the circular economy. The progressive potential of all such engineering programmes is governed by the political-economic framework.

Is degrowth the answer?

The insufficiency of engineering and green growth programmes has informed the waxing interest in “degrowth” strategies. This term is not intended to suggest that all economic sectors should shrink, but that for society-nature relations to regain some balance, the unsustainable global use of materials and energy must radically reduce, and in an egalitarian manner.

As the scale of the environmental crisis grows more daunting, even moderate voices — not degrowthers — have recognised that certain sectors, such as shipping and aviation, will have to be cut to virtually zero over the next 20 or 30 years.

What does this mean for critical minerals? According to degrowth advocate Jason Hickel, political means should be forged through which to plan priority sectors.

Reducing luxury and wasteful sectors such as SUVs, aviation and fast fashion would free up critical materials for the green transition. “Factories that produce SUVs could produce solar panels instead,” suggests Hickel. “Engineers who are presently developing private jets could work on innovating more efficient trains and wind turbines instead.”

Such practical examples highlight the possibility that today’s predictions of utterly unsustainable materials throughput by 2060 could at least be revised downward.