The world is looking to break its geopolitically risky dependence on imports of rare earth metals from Russia and China as East and West drift into an increasingly fraught showdown. Kazakhstan may prove to be the best bet of sourcing these crucial materials from a nominally independent provider.

The Central Asian country is second only to Russia when it comes to rare earth metal deposits and production, an essential component in the construction of electric cars, airplanes, computers and a long list of other everyday goods. The need to find new rare earth metal supplies became particularly acute after US plane-maker Boeing recently suspended titanium purchases from Russia on which it is heavily dependent.

Rare earths are hard-to-find elements and minerals essential to the production of the high-tech gadgets that drive the world’s economy. These unique minerals appear to be concentrated in their geological distribution in the heart of north-Central Asia. That makes the neighbour of western China – Kazakhstan – the prime locations to look for them.

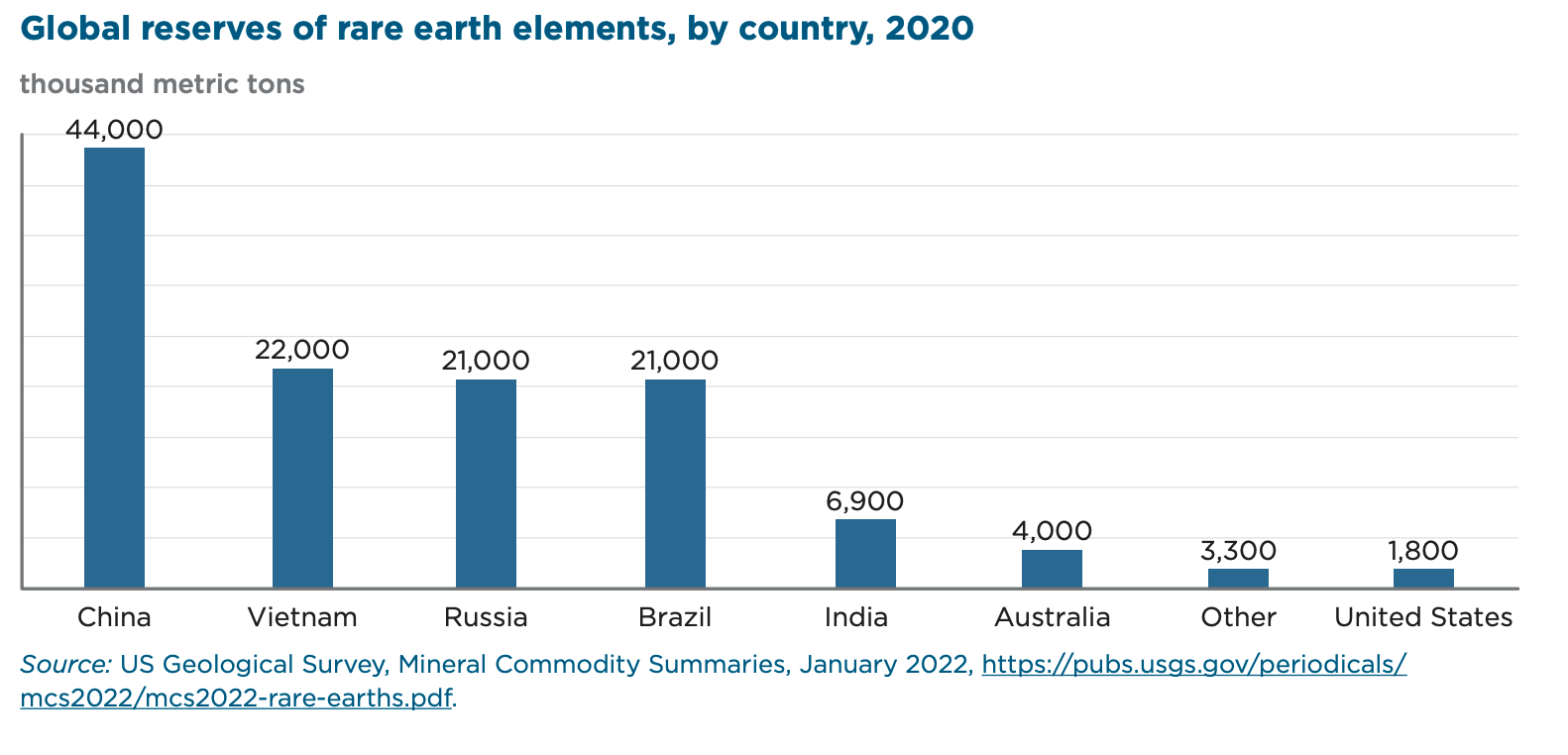

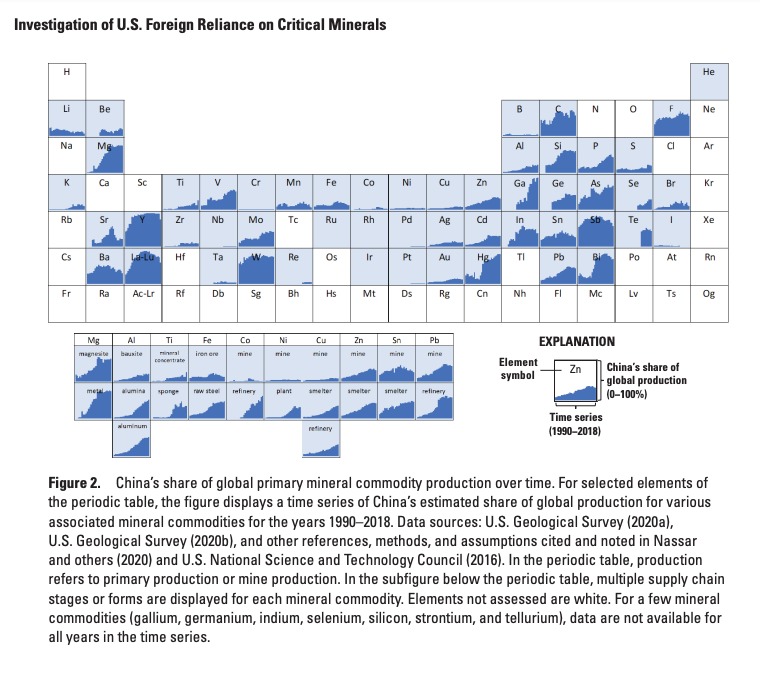

For years, China had effectively monopolized world supply and dominates in both the share of deposits (chart) of these elements and the processing and production of them (chart), accounting for more than 90% of the rare earths sold annually.

But with the supply and production so dependent on China, the world’s rare earths miners are seeking sources outside China, which is fast becoming a national security issue. Rare earths can be produced from uranium tailings, which means countries rich in uranium, such as Kazakhstan, are the most likely places to find them. Kazakhstan is the largest uranium producer and exporter in the world, and as the globe’s ninth largest country in terms of land mass, there are plenty of new places to look for rare earths.

In many metals Russia is also already one of the dominant suppliers or has significant market power. It supplies a tenth of the world’s aluminium and copper, and a fifth of battery-grade nickel. Its dominance in precious metals such as PGM metals, that includes palladium, key in the automotive and electronics industries, is even greater.

By luring foreign direct investments into this sector, Kazakhstan is hoping to improve its place in the rare earth metals market.

“We believe that taking into account the new concept, ESG standards (environmental, social, and corporate governance), as well as the needs of Kazakhstan and the current situation in the world, the new growth points for attracting investment will be rare and rare-earth metals industries and green energy,” wrote the chair of the Investment Committee at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ardak Zebeshev in his LinkedIn post on June 24.

US reliance on rare earth elements

The US remains particularly vulnerable to disruptions in the global rare earth minerals supply chains, as it is heavily reliant on foreign sources to meet domestic demand for a large and growing number of mineral commodities that are critical for its economy and national security.

Ever expanding sanctions and the Western resolve to further restrict cash flowing into Russia to finance Putin’s war in Ukraine have made it apparent that domestic supply of just about everything should be racing to the top of the priority list.

The US Geological Survey report on US Foreign Reliance on Critical Minerals says that the United States imports 35% of its palladium, a critical rare element in catalytic converters, from Russia, more than any other country. Moreover, the US produced 0.7% of nickel worldwide in 2020 and 2021, but imports most of its nickel from Canada. It even relies on Russia for 16% of its uranium.

However, previous reports suggested that US president Joe Biden’s administration is lobbying Congress for a $4.3bn spending plan to buy enriched rare earth elements directly from domestic producers to phase out Russian imports. Russia has also reportedly considered an uranium exports ban as a possible counter-sanction.

But all is not lost as various Western manufacturing companies can over time start producing replacements to overcome that supply challenge.

Uranium

Kazakhstan is by far the largest producer of uranium, mining 21,810 tonnes in 2021, according to the World Nuclear Association. Next comes Namibia with 5,743 tonnes, Canada with 4,692 tonnes and Australia with 4,192 tonnes. Uzbekistan follows with 3,500 tonnes, then Russia with 2,635 tonnes and Niger with 2,248 tonnes. This means that about 75% of uranium comes from Kazakhstan, Canada and Australia – all neutral or Western affiliated countries.

The country’s uranium national champion Kazatomprom is the world’s largest uranium miner and seller of natural unrefined uranium, providing over 40% of global primary uranium supply in 2019 from its operations in the Kazakh deserts. Kazatomprom’s uranium is used for the generation of nuclear power around the world.

There are currently 56 identified deposits in Kazakhstan that host reserves and resources in excess of 450,000 tonnes of uranium. Kazatomprom’s operations currently mine uranium from 14 of those deposits, of which one deposit has been fully depleted and is now in the decommissioning stage, while the remaining 13 deposits are being actively developed and mined.

Each of Kazakhstan’s uranium deposits differ in terms of certain geological features, depth, and value. However, based on common geological settings, genetic traits, and territorial isolation, all are generally considered to be sandstone-hosted roll-front uranium deposits occurring in six provinces: Shu-Sarysu, Syrdariya, North Kazakhstan, the Caspian, Balkhash, Ili.

Unlike the underground shaft mining or open-pit mining methods, the development of uranium deposits by In Situ Recovery (ISR) method, used by Kazatomprom, has little negative effect on the surface: there is no soil subsidence and disturbance, and no surface storage of low-grade ores or waste rocks. The major processing steps to extract the uranium take place deep underground (hence the term “in-situ”), resulting in lower production costs and an inherently higher level of health and safety performance due to lower mining risks. In addition, ISR in Kazakhstan does not require liquid waste or tailings management facilities. Upon depletion of the resource and completion of mining activities, Kazatomprom’s remote mine site locations are restored to their pre-mining state, both above and below ground.

When asked about concerns over security of supply and Russia’s involvement in Kazakh uranium projects, Kazatomprom’s chief commercial officer, Askar Batyrbayev, said that Rosatom has been excluded from any imposed sanctions so far.

“In terms of that, there have been no disruptions in operations. We have five joint ventures with the Rosatom group. All of them are operating normally. Kazatomprom is nevertheless taking measures in case of possible future sanctions on Rosatom that could impact Kazatomprom’s production,” Batyrbayev noted.

The uncertain future availability of Russian fuel and processing services amid the Ukraine war and related sanctions has brought concerns related to security of supply for Western utilities, driving an increase in both spot and term market activity.

Kazatomprom recently raised its revenue forecast to KZT790-810bn ($1.78-1.83bn). Previously, it was expecting KZT610-630bn.

“As a result of the geopolitical developments stemming from the Russia-Ukraine war, spot price rose to $58.30/lb U3O8, a level not seen since April 2011,” a company official said.

EV metals: lithium and nickel

With the demand for EVs growing rapidly, the demand for commodities used for EVs is also expected to grow.

Based on the type of EV, different battery types could be used. Most batteries used in EVs are lithium-ion batteries. The minerals needed for these batteries can differ based on the chemistry of the cathodes, but nickel, lithium, cobalt, graphite, and manganese are considered to be the key materials needed to make these batteries.

Russia supplies about 10% of the world’s nickel and Russia’s Nornickel is the world’s biggest supplier of battery-grade nickel at 15%-20% of global supply, according to JPMorgan analyst Dominic O’Kane as cited by Reuters. NorNickel is also a leading producer of PGMs (platinum group metals). All these metals are crucial for the production of electric cars.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecast earlier this year that nickel demand in electric vehicles (EVs) will grow by a factor of eight from 2020 to 2030.

The threat to Russian nickel exports caused the biggest crisis on the London Metals Exchange (LME) in decades at the start of the war, after the world’s biggest metal exchange was forced to halt trading after nickel prices topped $100,000 per tonne on March 7.

The surge in prices was blamed on short covering by one of the world’s top producers and cost brokers hundreds of millions of dollars in losses. Amid market panic sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, buyers are scrambling for the metal crucial for making stainless steel and EV batteries.

The Shevchenko mine, a largest mine in the north-west of Kazakhstan, represents one of the largest nickel reserves in Kazakhstan having estimated reserves of 104.4mn tonnes of ore containing 0.78mn tonnes of nickel metal.

Kazakhstan already exports its nickel reserves to countries in Europe. European Union imports of nickel from Kazakhstan was $518,000 during 2021, according to the United Nations COMTRADE database on international trade.

There were excesses of the maximum allowable concentration of nickel in water samples in Kazakhstan, the Minister of Ecology, Geology and Natural Resources of Kazakhstan, Serikkali Brekeshev, reported in July 2022.

Kazakhstan also recently has allocated more than $1mn for geological exploration aimed at finding lithium, a rare metal that the electric car industry desperately needs for battery production.

There are seven lithium fields in Kazakhstan (Yubileynoe, Verkhne-Baymurzinskoe, Bakennoe, Akhmirovskoe, Medvedka and Maralushenskoe). All of them are in the East Kazakhstan region. If geological exploration at Kara-Ayak and Muncha, the two new potential lithium fields succeeds, the country will have nine confirmed lithium sites for further development.

Kazakhstan currently has co-production agreements with leading companies in Japan, Germany and France to develop rare earths needed for production of electric cars in Kazakhstan. Japan has built a major rare earths production factory at Stepnogorsk in northern Kazakhstan to turn out dysprosium, a vital rare earth needed to make motors for electric and hybrid vehicles among other uses.

“We think that there is a very good investment climate in this country and that consequently Japanese companies can make long term investments here,” Yerzhan Ishanov, business development manager for Central Eurasia for Sumitomo Corporation, said.

Aviation metals: titanium

While Russia has large shares in the global supply of many metals, none are as important as those in the production of titanium and titanium forgings.

(As some readers have pointed out, titanium is not actually a rare earth metal, but we are including it here as it is an exotic metal and subsject to all the same issues as rare earth metals.)

Russia is the third-largest titanium producer with a share of around 13.5% after China and Japan, and Ukraine has a share of 2 to 2.6%. Russia and Ukraine combined account for 16% of global output.

Russia holds a key role in the titanium market and titanium is extremely important not just for commercial aircraft but is also used for the production of defence equipment and as a result is of paramount importance for national security. An obvious sanctions target, thanks to Russia’s importance in the supply chain the European Union removed restrictions on Russian titanium major VSMPO-Avisma from the seventh sanction package at the last minute in July in order not to disrupt the market. Russia is deeply embedded in the global metals market in general making these materials hard to sanction.

Titanium and titanium alloys are highly prized for their very high weight to strength ratio that makes them the ideal material for building planes, spacecraft and the defence sector in particular.

The US and European aviation sectors are likely going to struggle without access to Russian titanium.

Titanium alloys account for approximately 15% of the Boeing 787 airframe by weight. In the Airbus A350XWB, it is about 14%, and is used in landing gear, pylons, attachments, door surrounds, frames, and other parts.

Russian production of titanium is so important that Boeing has made major investments into Russia, producing many of its parts for planes as Russian facilities in partnership with VSMPO. It set up the Boeing-VSMPO Innovation Centre in 2000 as well as a joint venture, Ural Boeing Manufacturing, in 2009, on the site of the VSMPO factory, which was expanded in 2018 to produce more parts.

The US plane-maker announced its suspension of purchases of titanium from Russia and closing down its representatives in Moscow and Kyiv. Boeing has been trying to diversify its titanium supply in recent years, and it said it had enough of the metal on hand to keep making commercial aircraft in the near term.

Kazakhstan has large reserves of titanium as well. It exported $124mn worth of titanium in 2020, making it the eighth largest exporter of titanium in the world.

Titanium production in Kazakhstan started in the former Soviet Republic in 1965 in Ust-Kamenogorsk in the east of the country at the foothills of Altai mountains.

In addition to titanium, it also produces magnesium, vanadium, and scandium – the rarest earth elements.

The stage of production of titanium sponge is the main stage in the production of metal. Kazakhstan is among the six countries, owning the technology of manufacturing titanium sponge (China, USA, Russia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Ukraine).

Increasingly, customers around the world will likely be turning to technology that includes a little bit of Kazakhstan.

Rare earths are critical to the manufacture of many high-tech items, but getting them from the ground to your laptop isn’t easy. They are also often radioactive, and the disposal of the contaminated water from extracting them has angered environmentalists. It will be interesting to see how Kazakhstan will overcome the obstacles to producing these vital inputs for the high-tech world.